Disaster Preparedness & Resilience Through Community

We are well aware of the climate change induced challenges that we now face. Building resilience through preparedness and adaptation is something built into the DNA of Landcare.

This piece aims to offer some insight into what Landcare is already doing in relation to disasters, and that because of the Landcare ethic, the movement and the model (National Landcare Framework), Landcare continues to offer so much to disaster resilient communities and landscapes.

“I see Landcare as providing many of the ingredients that support individuals and communities in challenging times,” Peter Pigott, Community of Practice and Events Coordinator at Landcare NSW reflected after attending the 2024 Australian Disaster Resilience Conference in Sydney.

“Placemaking, landscape preparedness, and connection within community and to landscapes are all critical to disaster resilience. There is increasing research linking the strength of social capital and what is known as ‘social infrastructure’ to better outcomes in and following disaster.”

Landcare groups and networks are placemakers—bringing the community together to co-create a renewed sense of place, identity, and connection to the land. Daniel Aldrich’s findings on social infrastructure and disaster resilience highlight that the communities with strong pre-existing ties and collective involvement in land management were more resilient in the aftermath of the fires.

Landcare also plays a key role in disaster preparedness. The focus on proactive environmental care and sustainable land management practices, such as revegetation, erosion control, and fire management, helps communities mitigate the risks of future natural disasters. Communities involved in Landcare projects are not only better connected, but also more knowledgeable about their local environment, which enhances their capacity to anticipate and respond to future threats.

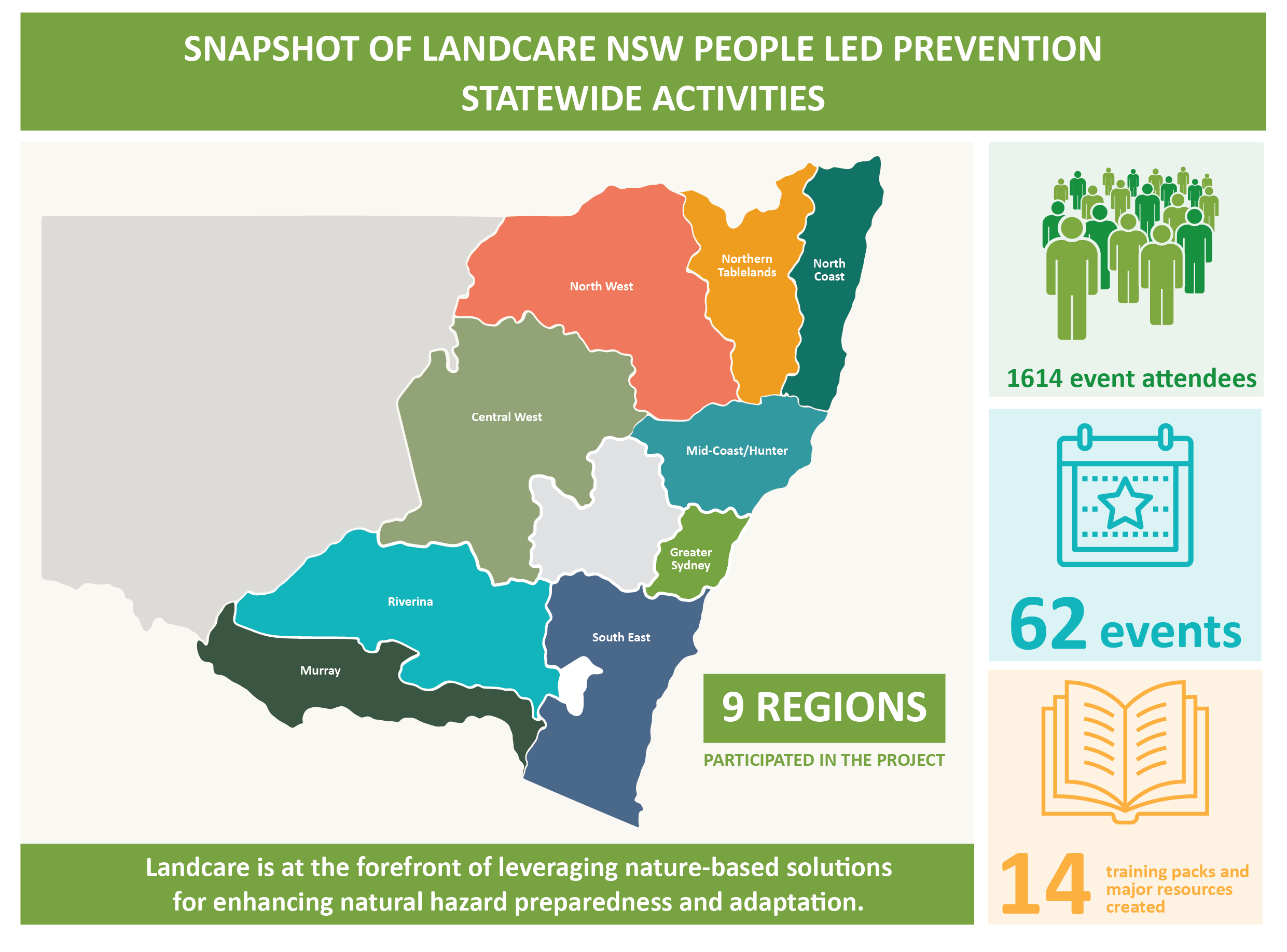

Landcare NSW’s People Led Prevention Project, funded through the NSW and Australian Government Disaster Risk Reduction Fund, has worked with Landcare communities across NSW to build knowledge and capability for disaster preparedness and nature-based solutions to mitigate hazard risks. This project leaves a legacy of resources for communities to tap into as they explore what it means to be prepared.

There is an increasing number of Landcare partnerships with First Nations communities, sharing practices of cultural fire that have a tangible impact on fuel loads and build positive relationships in community.

In the aftermath of disasters, rebuilding the social fabric of communities is as crucial as restoring physical infrastructure (Stilger B, 2017). Following the 2019-2020 fires and 2022 floods across many parts of the state, numerous Landcare groups across NSW mobilised to restore the natural landscape and help rebuild the social fabric of fire-affected and flood-affected communities.

“A new Landcare group is forming following devastating flash flooding in the town of Eugowra in the Lachlan Valley in the Central Tablelands region of NSW,” Peter recounts following a conversation with a Local Landcare Coordinator.

“In a town where 80% of homes and businesses were damaged, the formation of the new group and the support from the Landcare Coordinator is contributing directly to disaster recovery. Getting together to have a little fun is one of the activities of this Landcare group and might be one of the most important aspects of their Landcare work at this time.”

There are times in community where we just need to be able to get together and enjoy being with one another. Landcare does this too. Community events centred around a shared task, good food and an element of fun are such important parts of the wellbeing of the Landcare group and have deeper impacts in the context of disaster resilience.

Dr. Rob Gordon, a psychologist specialising in disaster and recovery, highlights the crucial role of community and social connection in the healing process after disasters. He argues that psychological recovery is deeply intertwined with social recovery, as people often process their trauma and grief through community support and shared experiences. Landcare’s collective environmental action aids both ecological and psychological recovery. The meaningful, shared work aspect of Landcare provides a framework for social healing.

In 2024 the Sydney Environment Institute explored how self-organising systems like community Landcare groups and networks can be supported to build long term resilience (Webster et al.,2024) and offer us encouragement, recommending:

- Advocating for robust support mechanisms for self-organised community networks to enhance their disaster response capabilities and overall resilience.

- Emphasising the promotion of social cohesion within communities to cultivate a culture of collaboration and mutual support during times of crisis.

- Urgently addressing the challenges posed by climate change to mitigate future disaster risks and build sustainable, long-term resilience within communities.

The future we face is one that we need to be prepared for. We know that being connected to each other, to community and care, to place, and to nature is part of being prepared in a way that will minimise the impacts of disasters on us and on Country. Landcare does this well. What is possible when we embrace our role as a key ingredient in building disaster resilient communities and landscapes?

Landcare NSW Natural Disaster resources are located here.

References:

Aldrich, D. P. (2012). Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery. University of Chicago Press.

Webster, S., Pittaway, E., Gillies-Palmer, Z., Schlosberg, D., Matous, P., Longman, J., Howard, A., Bailie, J., Viney, G., Verlie, B., Celermajer, D., Naderpajouh, N., Rawsthorne, M., Joseph, P., Iveson, K. and Troy, J. (2024) Empowering Communities, Harnessing Local Knowledges: Self-Organising Systems for Disaster Risk Reduction (April 2024). Sydney Environment Institute.

Gordon, R. (2004). The social system as a site of disaster trauma. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 19(4), 16-22.

Silberberg, S., Lorah, K., Disbrow, R., & Muessig, A. (2013). Places in the Making: How Placemaking Builds Places and Communities. MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning.

While Australia grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic which poses an acute threat to our wellbeing and way of life, climate change and its many manifestations remains a serious and chronic threat to life as we know it.

While Australia grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic which poses an acute threat to our wellbeing and way of life, climate change and its many manifestations remains a serious and chronic threat to life as we know it.